"Unfettered by object status, Conceptual artists were free to let their imaginations run rampant. With hindsight, it is clear that they could have run further, but in the late sixties art world, Conceptual art seemed to me to be the only race in town."

—Lucy Lippard, “Escape Attempts” (1997)

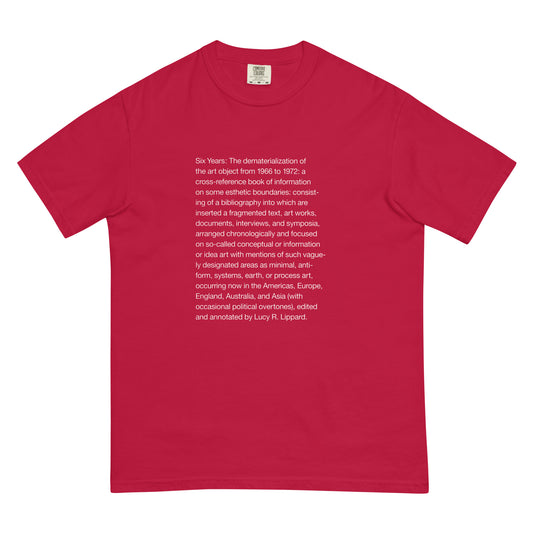

In the preface to her landmark book, Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972 (published in 1973)—perhaps the most influential chronicle of conceptual art as it happened—Lucy Lippard defined conceptualism as an art in which “the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious, and/or ‘dematerialized.’” Emerging out of Pop art and minimalism’s double-pronged attack on the pieties of high modernism (along with other sources in the historical avant-garde, especially the Dadaist readymades and language games of Marcel Duchamp), conceptual art had a revolutionary edge that was tied up with the political ferment of the times—antiwar protest, civil rights, psychedelic counterculture, and the feminist movement—despite the absence of explicit political content in most conceptual works.

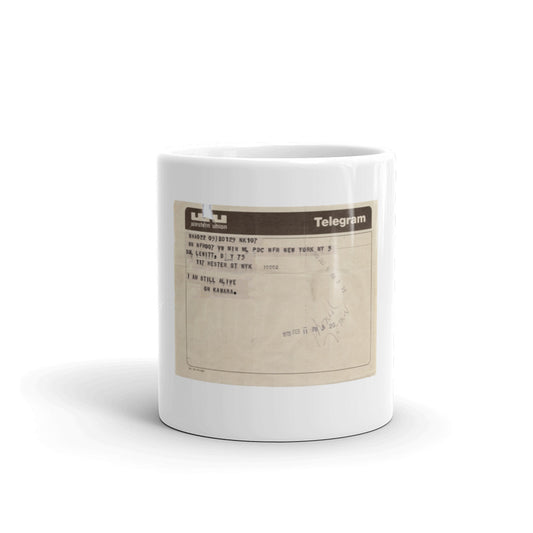

Conceptualism’s redefinition (or elimination) of the art object moved art out of the established, commercial gallery-museum-auction nexus and into the world at large—whether that meant urban public space or the remote salt flats of Utah—without necessarily bringing it to a mass audience. Conceptual art circulated within new, decentralized social networks forming internationally, supported by a burgeoning scene of artists’ books, small magazines, and artist-run gallery spaces. Conceptual artists latched on to new communications media like videotape, early computers, Xerox copiers, and Telex machines, facilitating a new speed of information exchange and a sense of “ideas in the air,” as artists around the globe, often unknown to each other, began to spontaneously produce work on similar wavelengths.

Information theory and cybernetics were a crucial source, and the idea that “information art” had something to do with the emergence of “information technology” (then still in its infancy, with the personal computer a far-off dream) was central to some of the first major exhibitions of conceptual art presented in New York, especially Jack Burnham’s Software at the Jewish Museum in 1970 and Kynaston McShine’s Information at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971. However, rising anti-war sentiment, which associated high technology with the military-industrial complex, soon put an end to the more techno-utopian tendencies within conceptualism, as politically active artists like Hans Haacke switched from exploring natural and technological systems to social and economic ones.

Much conceptual art had a neutral, bureaucratic, and pseudo-scientific look—lists, diagrams, descriptions, counting, and repetition proliferated—related to the mimicry of information systems. Perhaps ironically, this anti-aesthetic, with its anachronistic trappings of obsolete technology, has its own aesthetic appeal from the vantage point of the present. Even at the time, some conceptual artists, like Bas Jan Ader, used formal neutrality as a way of smuggling beauty, emotional feeling, and even a romantic sense of the sublime through the back door.

This anti-aesthetic quality also relates to the anti-commodity position inherent to first-wave conceptualism, a rejection of (in Lippard's words again), “the greedy sector that owned everything that was exploiting the world and promoting the Vietnam war.” Another irony, however, is that, in collapsing art and life, work and play, conceptual artists (especially those like General Idea and N.E. Thing Co. who adopted corporate personas) intuited the eventual commodification of experience itself and the rise of information as a primary commodity within 21st-century capitalism. In a way, conceptual art took note of the supremacy of marketing and publicity over the objects being promoted—and, since the advent of conceptual art, artists have developed countless novel ways to package and promote their performances, videos, photographs, installations, and personalities.

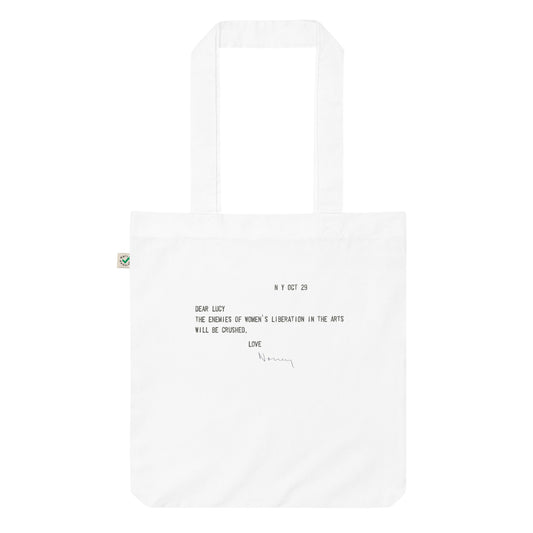

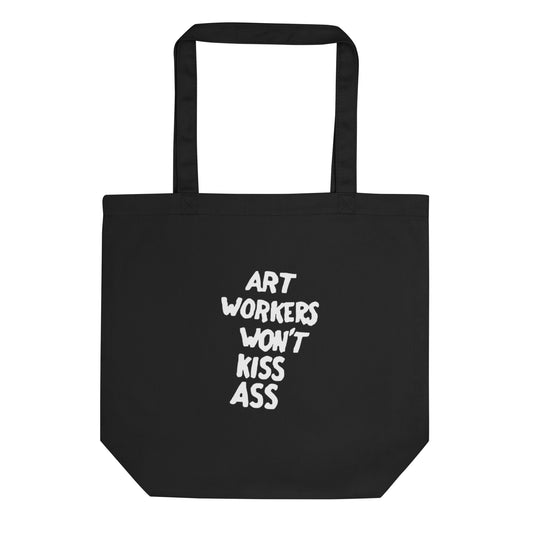

Indeed, conceptual art marked a moment of increasing professionalization within the arts, as advanced degrees and theoretical savvy became increasingly necessary for a career. Some have theorized artists as the ideal "creative" workers (precarious and exploited but entrepreneurial and mobile) of the neoliberal era. However, as activist groups like the Art Workers Coalition—which counted Lippard and numerous conceptual artists among its members—proved, artists asserting their identity as workers can allow for productive forms of solidarity.

The ”post-medium condition” (Rosalind Krauss’ term) inaugurated by conceptual art has also meant that conceptual art played a crucial role in the development of “contemporary” art as an entity distinct from “modern” art. Indeed, one could chart a history of contemporary art as a whole through the heuristic of immateriality, in which we see art production shift, from the late 1960s onwards, away from a focus on the craft of specific media (painting, sculpture) towards a post-medium, post-studio, or research-based practice that might equally employ handcrafted, fabricated, or readymade objects and images, installation, performance, video, digital media, or various combinations thereof.

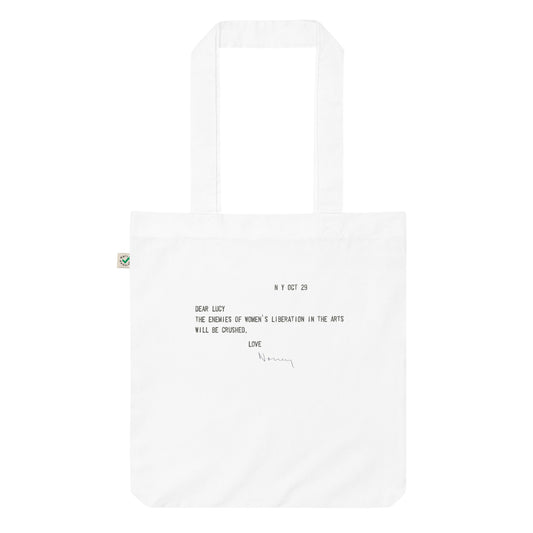

This collection, however, focuses on the early, “pure” conceptual art produced in the period (1966-1972)* covered by Lippard’s Six Years, the kind associated with typewritten (or handwritten) pages and grainy black-and-white photos—the surprisingly physical mediums for concepts that, in their ideal form, might have been best transmitted by telepathy. (Robert Barry did attempt this for his Telepathic Piece at Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University in 1969). Douglas Heubler—an iconic figure of the movement’s early phase—famously stated, “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” On one hand, this collection of merchandise betrays his noble impulse. On the other hand, Mel Bochner also wrote that “no thought exists without a sustaining support.” We contend that the history of conceptual art is full of ideas, more or less interesting; these shirts, hats, mugs, tote bags, pins, and postcards merely support them.

*With one exception: General Idea formed in this period, but the GI items in this collection use images dating from 1975 and 1981-82.

Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out